Managing Managers and Teams Notes

Managing Managers Notes⌗

[This is a bunch of bullet points on managing managers and teams, and that ended up being the foundation of a large set of ‘mental models’ I wrote. More on how to do that later…]

Preface: Congratulations!⌗

- Our desire for organizational stability is our worst instinct.

- Seeing an org as a fixed cost is precisely the wrong mindset, you should be creative with your organization and engage with it like a ‘work product’.

- Right now there is someone on your team who is doing great. They could do more if you let them, but they aren’t because you’re happy with the work they’re doing. That’s the wrong mindset for growth. Are you pushing themselves to the point where they’re starting to fail? If not, they won’t understand their capacity, and you won’t realize the extra ‘yield’ you’ve already got.

- As a rule, you should double the capacity of your leadership every year. That’ll stay ahead of growth (linear) and cross-functional complexity (quadratic).

- Let people impress you. Stretch them. When things start to fail, that’s signal on where to hire.

“Congratulations on your transition. We call it a transition for PR reasons, but it’s actually a brand new job, and your new API is people”.

Tuning Yourself⌗

-

People leave managers, not companies.

-

Figure out your strengths and weaknesses

- Build many feedback loops. Always be getting signal. Tune yourself. Breakdown inertia to building that feedback loop.

- Self-reflection: serious thought about ones character, actions, motivations.

-

Why bother? You’re reducing the uncertainty you have about how you are seen, how you are performing within your environment.

-

Build many amazing feedback loops. Always be ‘pulling’ signal. Always be tuning.

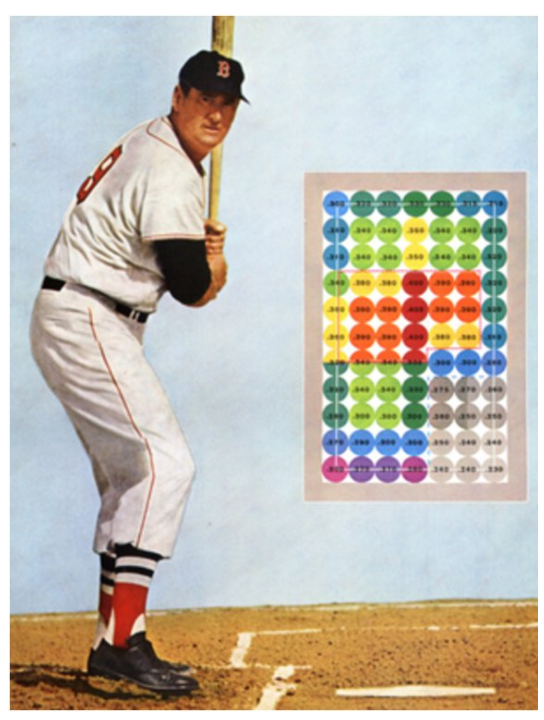

- 400-500 sensors, 2GB of telemetry per race

-

Build a brilliant mental simulator. Perform mental simulations on everything.

-

Get a mentor and a coach.

- Learn the difference: mentoring is long term, strategic, requires relationship building. Coaching is task orientated, Socratic method, performance based.

- They will lead you to self realization of your blindspots, strategize and plan for your career.

- I got a coach.

-

Learn how to be a mentor and a coach.

- Given we only consciously observe when asked (by others, or ourselves) or motivated to focus, coaching and the Socratic method works amazingly well.

- ‘We believe we’re seeing the world fine until it’s pointed out to us’.

- Best book on this is: [https://www.amazon.co.uk/Incognito-Secret-Lives-Brain-Canons-ebook/dp/B004SP1UEI/]

- Your primary job is to reduce the uncertainty your coachee has of their environment

- Difference between therapist, mentor and coach:

- Therapist: understanding current situation

- Mentor: skill transfer, directional guidance

- Coach: Understanding and transformation

- Cox proposes the Experiential Coaching Cycle, which has three substantive ‘constituent spaces’; i.e., Pre-reflective Experience, Reflection on Experience and Post-reflectve Thinking (where each space is “a hiatus where events occur or reflection happens”); and three major ‘spokes’ or transition phases; i.e., Touching Experience, Becoming Critial, and Integrating (p. 5)

- Pre-reflective Experience “informs everything the clients eventually reflects on and talks about in the coaching”; Reflection on Experience “involves deliberation and dailed descriptive articulations of experiences and their associated perceptions and emotions”; and Post-reflective Thinking “involves logical, cognitive processing, such as metacognitive activity and post-rationalisation, this also encompasses the effectiveness of mindfulness and other embodied practices” (p. 6).

- Touching Experience is “an articulate attempt to grasp feelings or intuitions which appear to be buried or submerged”;

- Becoming Critical is “encouraged by critical, rational thought that aims to move the client towards a more critical stance”; and

- Integrating is “testing ideas and making changes” (p. 7).

-

Articulating the experience through listening.

-

Cox distinguishes between ’empathetic’ listening (reproductive) and ‘authentic’ listening (constructive)

-

Clarifying: In therapy, the main function is to enable the helper to gain an accurate picture of the client’s reality in order to make decisions about what course of ’treatment’ to provide. In coaching it is clients who need to order and reorder their thoughts and create a picture, and so they need to be provided with opportunities to discover new ways to do this. (p. 71)

- Critical:

- Reflection

- Cox distinguishes between phenomenological reflection, which involves accepting the essential meaning of pre-reflective experience (p. 76-77) and critical reflection, which involves “challenging existing perspectives” (p. 74). Sometimes, however, “the relationship between describing and analysing is so close that in practice they will occur in close succession, perhaps iteratively”

- Critical:

-

You’re unconscious self is shaped by your genetics, and your environment. But you can tune that too.

- ‘Steering wheel example’

-

Ask fucking good questions

-

Journalism ‘five W’s.

-

Always be asking why.

-

‘Engineer shows up late every day…’

-

-

But learn how to be a brilliant listener

- Observe how often people ’talk past each other’

- Deeply understanding someone’s position is required for empathy

- This means putting aside your ‘agenda’. An agenda is like an invisible wall between you and the person.

- Learn about ‘power dynamics’ and how that affects your conversations.

- One person doesn’t create the dynamic, you both do.

- Vulnerability is a tool to rebalance power. There are others.

- (Added bonus: it’ll make your life relationships better too!)

- ‘Yes, but’ a classic signal that someone may not have felt heard or understood

- To reduce someone else’s uncertainty about their world, you must first understand the shape of that uncertainty (their biases, how distant they are from the truth). A classic error is to transmit feedback directly, without first moulding the feedback to best adapt and reduce their current state of uncertainty.

- Example: “John manages Brian, and Brian has been doing the same job for two years, and is looking to grow in new dimensions. Brian likes his job. John wants to communicate to Brian that he should move out of his current role into a brand new team, and that John has a great plan to manage that transition safely and effectively. John spends a little bit of time communicating the why, and a lot of time communicating the great plan he’s come up with. Brian’s uncertainty about his competency and value in John’s org grows wider as a result, and Brian becomes anxious.”

- John should have done two things: identified the uncertainty, and focused most of the conversation on reducing that uncertainty: “I believe in you. I’ve been looking for a while now to identify new growth opportunities for you. I know you’re enjoying your role, and frankly, you’re doing an excellent job, but I believe over time you’ll grow and enjoy this new one a lot more, and the growth you’ll have in this new role will open up further opportunities like X”.

-

Deeply understand relationships:

- John Gottman

- Four horseman: criticism, defensiveness, contempt, stonewalling

- Destructive communication styles: harsh startup, flooding, body language

- It’s not trust, it’s safety.

- Bids for connection: ‘I want to connect with you, so please give me your attention’. Rejected bids lead to poor relationship outcomes, accepted bids like ‘I understand you, I want to help you, I accept you, I’m interested’ lead to positive outcomes.

-

Crucial conversations:

- Learn the art of the ‘metaconversation’

- More crucial, more likely to be silent of violent

- Safety is important: mutual purpose ‘you care about their best interests and goals’, mutual respect ‘you care about them’.

-

Now learn the manager job:

- Show care by understanding what is most important for each person’s experience

- Support people in finding opportunities to develop and grow based on areas of strength and interest

- Set clear expectations and goals for individuals and the team

- Give clear, actionable feedback on a timely basis

- Provide the resources people need to do their jobs well, and actively remove roadblocks to success

- Hold people and the team accountable for success

- Recognize people and teams for outstanding impact

- Holding people accountable:

- Set expectations

- Invite commitment

- Measure progress

- Provide feedback

- Link to consequences

- Evaluate effectiveness

-

Focus on continuous improvement via feedback loops:

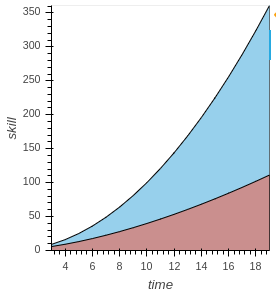

- Area under the red curve: growth trajectory I typically see when managers try to ‘wing it’. Area under the blue curve: growth trajectory when focusing on continuous feedback driven improvement. Learning == effort + feedback loops + reflecting on failure + understanding successes.

- Effort is expensive, honest feedback loops are rare, reflecting on failure is confrontational to your ego, and success isn’t always earned (it’s sometimes random).

-

Learn to Learn

- I’d define learning as the process to which one comes to deeply understand something. People with deep understanding usually exhibit these properties:

- Are usually able to effortlessly communicate things at any level of abstraction.

- Have absorbed the topic through many different lenses or viewpoints, and are often able to hold many hypotheses in their heads at once.

- Are able to articulate what they don’t know, and where the limit of their understanding is.

- Sometimes have their own unique perspective on a topic, synthesized from either their own experience, or by connecting disparate topics together to create something new.

- Read well:

- Most of us are experts at comprehending words written on a page, and we’re pretty good at synthesizing those words into facts that can be stored away in memory, but we’re over-exercised on fast-food content: entertainment news, rambling and superficial blog posts, Twitter. Indexable facts of information, but they don’t lead to understanding of a complex topic.

- The distinction between reading for information and reading for understanding is important. Reading for information, you become informed. Reading for understanding adds a few more important things: you know why it’s the case, what connections are with other facts (how is it the same, how is it different, and in what respect), and why its important.

- I’d define learning as the process to which one comes to deeply understand something. People with deep understanding usually exhibit these properties:

-

Coaching examples:

- “I’m looking for guidance on how to manage up. My direct manager is leaving the company, I have a new manager who’s my Director. The pulse results from the team are concerning: ‘my leaders are transparent’ scores are low, and anecdotally they’re saying they don’t understand the vision and direction that the org is taking. I’m looking for feedback on how to deliver this message in a good way”.

- Two ways this coaching session can go: 1) talk about ways to have a potentially difficult conversation, or 2) coach the individual to understand ‘why’ he’s blocked. In this instance, he was scared, and he was scared because his default modus operandi is to build a relationship of safety first and then start to have these sorts of conversations. I asked him what may be causing him to be scared, given all rational analysis of this situation is that his director will 99.9% of the time welcome the feedback.

- “I’m working with an important client on a project. I have a technical resource that I’m using from a different org whom I’ve worked with before. This person is disengaged now, not showing up, and it looks like the project may not ship on time. What do I do?”

- Again, two ways: coach the person on how to get resources from elsewhere, or talk to his manager or talk to him or whatever it is. Second way is more interesting: what prevented this person from having an honest conversation with the technical resource and figuring out why he was disengaged?

- “I’m looking for guidance on how to manage up. My direct manager is leaving the company, I have a new manager who’s my Director. The pulse results from the team are concerning: ‘my leaders are transparent’ scores are low, and anecdotally they’re saying they don’t understand the vision and direction that the org is taking. I’m looking for feedback on how to deliver this message in a good way”.

-

We have this ideological understanding of conflict, where we say it happens when people want different things. But I think it actually happens when people want the same thing - the same promotion, recognition for doing the same job well, the same toy as a kid.

-

Recognize that conflicts are essential for great relationships because they are the means by which people determine whether their principles are aligned and resolve their differences.

-

Conflict/disagreement can happen if shared values aren’t well understood.

-

In all relationships, 1) there are principles and values each person has that must be in sync for the relationship to be successful and 2) there must be give and take. There is always a kind of negotiation or debate between people based on principles and mutual consideration. What you learn about each other via that “negotiation” either draws you together or drives you apart

Understanding Teams⌗

- Forming, storming, norming, performing

- Forming: high dependence on leader for guidance and direction. Little agreement on team aims other than received from the leader. Answer lots of questions about purpose.

- Storming: Team members vie for position as they attempt to establish themselves relative to the group. Clarity of purpose increases, but uncertainties persist. Power struggles, people not listening to each other, frustration etc. Frustration with weaknesses of other team members.

- Norming: Agreement and consensus is largely formed among team. Roles and responsibilities are clear and accepted. Commitment is strong. Team somewhat self reflective.

- Performing: Team is strategically aware, clearly knows what it’s doing, shared vision, strengths of the team and team members are known. No participation from the leader. Team is able to work towards the goal.

- The current potential of the team is the sum of all members strengths and ‘untapped’ yield.

- Learn timing and space. The richest, deepest conversations need space. Think of all the road-trips where you’ve had deep and meaningful’s.

- Team mind: working memory (information presented, discussed, moved on and forgotten); Long term memory; limited attention; has the ability to learn.

- Cares about identity, has ego, culture, bias etc.

- You’re responsible for setting the team composition. It’s one of the most important things you can do as a manager and a leader. To build that “performing” team, you need the right makeup of people all working on it

- Make sure you have ‘active protagonists’: they must be an active force on your team. A simple differentiation between active and passive: whether they cause things to happen or whether things happen to them.

- People don’t change that much. Don’t waste time trying to put in what was left out. Try to draw out what was left in.

- Four keys (First Break All The Rules pp 67)

- When choosing, select for talent

- When setting expectations, define the right outcomes

- When motivating, focus on strengths

- When developing, find the right fit

- Culture: ‘Culture is the behaviors you reward and punish’

- ‘If you didn’t build a consistent culture of humility, you failed to build an immune system against arrogance’.

- Collaboration:

- Most people confuse collaboration. Three distinct levels: coordination, communication, collaboration. Collaboration implies teams working together to achieve a common purpose.

- Coordination: least productive

- Communication

- Collaboration: most productive

- What the research says:

- Members of complex teams are less likely - absent other influences - to share knowledge freely, to learn from one another, shift workloads with flexibility, help others to complete jobs and make deadlines

- Teams above 20 people have decreased collaboration. 150+ or more usually don’t have much at all

- What helps improve collaboration:

- Executives/leaders who invest in supporting collaborative relationships and showing it.

- Exposing or making transparent the collaboration that happens at the “top”. i.e. share meeting notes from the leads meetings. etc.

- Trust is essential. Anything to build trust only increases the probability of successful collaboration outcomes.

- Being purposeful about designing the relationships you want, and ensure sufficient investment. i.e. track it, put people on it, define outcomes, hold accountable.

- Teams need a precise understanding of what it means to be a “healthy team”. As an example:

- We ensure psychological safety by:

- Ensuring that leaders of teams hold members accountable for inclusiveness and openness.

- Align people’s strengths to the teams needs

- Build diversity and tolerance into teams culture

- Hold leaders of teams accountable for moving from ‘storming’ to ‘performing’ within a reasonable time frame.

- Ensure all individuals deeply understand what is expected of them at their current level, and the next level.

- Work through conflict quickly, with empathy and understanding.

- Be intolerant of, and manage out individuals who are not maintaining safe environments for their peers.

- Optimizing for the whole, not the part. Support movement/change across the organization, even if it’s not locally optimal.

- We grow people by:

- Understanding how people want to grow and ensuring that their grow path has a reasonable probability of success.

- Help build an individual growth plan that’s lined up with the teams needs

- Differentiate between ‘being stretched’ and ‘setup for failure’.

- Ensure that leaders understand how to manage the anxiety of uncertainty of people in the ‘stretched’ category.

- We innovate by:

- Bold bets includes projects/goals that have a high degree of uncertainty, as opposed to risk.

- Risk: a state of uncertainty which is able to be measured.

- Uncertainty: a risk that is hard/unable to be measured.

- We understand the time horizons for innovation and categorize our bets into them.

- We execute by:

- Have a clear and measurable sense of what value these goals are providing to the organization.

- Goals will typically be 50/50 goals (the probability of hitting them is 50%).

- Break down goals into executable milestones, and regularly track how well we’re doing against them.

- regularly re-test assumptions we have made about ‘why’ and ‘how’ we’re achieving these goals.

- We will “fail-fast” if new information about assumptions or the goal changes the upside for the goal.

- We transfer all learning after failing-fast.

- We focus on high quality engineering.

- We ensure psychological safety by:

- Hold your teams and leaders accountable to those values and standards.

- Teams are about sociological stories (stories about people, groups, adaptation to the sociological situation) rather than psychological stories that are typically focused on the individual (overcoming difficult situations, pushing through barriers etc).

Leadership⌗

- What is leadership? Being able to think for yourself and act on your convictions.

- Leading. Meaning finding a new direction, not simply putting yourself at the front of the herd that’s heading toward the cliff.

- Thinking means concentrating on one thing long enough to develop an idea about it. Not learning other people’s ideas, or memorizing a body of information.

- You’re always signaling.

- As a leader, you set the tone. Hate conflict? You’ll try and strip the team of an opportunity to vent, air laundry and so on.

- ‘Decision on going to a War Room, lots of conflict, ‘guys let’s move on’.

- As a leader and manager, you set and direct the team values

- Communicate intent. Team members can then “read your mind”. Intent is used to improvise and adjust.

- Learn the different types and styles of leadership

- Authoritative leadership: mobilizes a team toward a common vision and set of end goals. “Come with me”.

- Affiliative leadership: bonding and belonging. “People come first”. When the team needs to heal.

- Coaching leadership: “try this”. Builds teams for the long haul.

- Coercive leadership: “do what I tell you”.

- Democratic: consensus through participation. “What do you think?”

- Your job as an org leader is to make your org a ‘stable molecule’. Unstable molecules take too much effort to hold together.

- Many successful, creative people aren’t good at execution. They succeed because they forge symbiotic relationships with highly reliable task-doers.

- Cold Starting a new team/career change (Good Boz note): An algorithm for ramping up quickly. First step, meet with the people on the team:

- First 25 minutes: ask them to tell you everything they think you should know. Take copious notes. Stop them to ask about things you don’t understand.

- Next 3 minutes: ask about the biggest challenges the team has right now.

- Final 2 minutes: ask who else you should talk to. Write down all names.

- First one gives you a picture of the teams work, and helps you build a framework for integrating information quickly. The nature of what people choose to discuss is very valuable signal about the problems the team face (it may be about the work, the organization, or the process).

- Second gives you a cheat sheet on where there is easy low hanging fruit to impress the team (our team meetings suck), and gives you a barometer for the broader challenges you’ll need to face over the months.

- Third gives you a valuable map of influence in the organization. The more often names show up and the context in which they show up tends to provide a very different map of the organization than the one in the org chart.

Goals, Planning, Decision Making⌗

-

Vision, goals, outcomes.

-

Always be setting context. Always.

-

The output of planning is an organization aligned around the plan.

-

“Nothing kills excitement like ambiguity”

-

Different settings require different communication strategies (individual vs. team).

-

Introduce signal and feedback loops in to the system: Pre mortems, post mortems

-

Goals must have a sense of being achievable. It’s easier for people to problem solve in discrete chunks.

-

Learn how to brainstorm. Never control the conversation. You can really get a sense for how messy the teams mind is from a good brainstorming session.

-

Listen to your team’s creative potential: when making movements towards new goals/directions, always encourage your team to bubble ideas and trust that they’ve probably got more derived insight than you do.

-

Become an expert decision maker:

-

Good decisions are measured by the process, not the outcome: a good decision is one that was sized and assessed rationally, where we’ve made reasonable judgements on all options, and their probabilities of occuring, and then made the rational call based on that. We too often conflate the outcome (good or bad) with the quality of the decision. Outcomes are probabilistic.

-

The goal (if we have one) is not to make perfect decisions but rather to make better decision than average. To do this, we required either good luck or better insight (more complete set of options or a better calculation of probabilities).

-

All decisions are bets.

-

Betting consists of choices, probability, risk, belief and decision. The rational process for betting is simple:

- Assess all (or as many) possible outcomes as possible (choices)

- For all outcomes, assign a probability of that outcome happening (probability)

- For all outcomes, calculate the ‘upside’ or ‘payoff’ relative to all other outcomes and calculate any downside also. (risk)

- Assess the size/stake/investment/commitment of the bet. (risk)

- Assess ‘how you’re being fooled’ – cognitive bias, incomplete information, deception (belief)

- Decide by finding the choice that has a payoff greater than the risk. (decision)

-

Not making a decision is also a bet (that the status quo has a higher payoff than what’s at risk)

-

Most bets are bets against ourselves – most of our decisions we are not betting against another person, rather we’re betting against all future versions of ourselves that we’re not choosing. We’re constantly deciding among alternative futures: going to the movies vs. staying at home. At stake in a decision is a return of money, time, happiness, health or whatever we value.

-

Risk: first articulated by economist Frank H. Knight in 1921: “something that you can put a price on”.

-

Uncertainty is ‘risk that is hard to measure’.

-

First level thinking: All you need is an opinion on the future “The outlook for the company is favorable, meaning the stock will go up”. Second level thinking does not accept the first conclusion: “What is the range of possible outcomes?” “What’s the probability I’m right?” “What’s the follow on effects?” “How could I be wrong?”. The Most Important Thing Illuminated

-

World Champion Chess Master Emanuel Lasker once said “when you see a good move… look for a better one”.

-

An important aspect to improving the odds of making good choices is the ability to distinguish between decisions within our circle of competence, and those on the outside:

-

-

Become an expert problem solver:

- Most problems are unstructured, which makes them very hard to solve. Ill structured if the initial state is not defined, or the terminal state is undefined, or the procedure for transforming the initial state into the terminal state is undefined.

- “What do you want to do with your life?” Unstructured in all senses.

- Environment shapes plans: stable environment more complex plan. Is complexity good? Fast moving environment

- Measure measure measure. Measurement is the science of reducing uncertainty, and is a probabilistic exercise. The cost of measurement should be lower than the benefit of better decision making.

- Consider which decisions are worth making: zone of indifference.

- Tactical: delay, option value, upside/downside

- Leverage points: Chess players are routinely looking for leverage: I have an opportunity to attack the queen (but not capture it), the leverage point is generating other opportunities for attack given the queen offensive.

- Alter the goal, it may generate new leverage points.

- Imagine shrinking the team by half - what changes?

- And review the decision (post mortem). Expertise is markedly improved when participants have a chance to review the decision, and the decision making process.

- Story: Expert chess players spend a lot of time reviewing decisions they made to improve their play for the next tournament. While practice may seem like the intuitive reason experts become experts, it’s actually purposeful review and criticism of their previous games decisions that get them there.

- Chess players learn through memory and experience where to concentrate their thinking. Elite chess players tend to be good at metacognition – thinking about the way they think – and correcting themselves if they don’t seem to be striking the right balance.

- Most problems are unstructured, which makes them very hard to solve. Ill structured if the initial state is not defined, or the terminal state is undefined, or the procedure for transforming the initial state into the terminal state is undefined.

-

Then after all that, realize that sometimes your role is to manage a coalition: “A manager is usually portrayed as a great decision maker - the scientific decision maker. She’s got her spreadsheet and she’s got her statistical tests and she’s going to weigh the various options. But in fact, real management is mostly about managing coalitions, maintaining support for a project so it doesn’t evaporate.”

-

In normal companies, the truth is whatever important people agree it is.

-

Think Ahead: it’s really easy to get bogged down in the details of some work and forget the purpose of what you’re actually doing. Step back regularly, and ask yourself questions to recall and clarify /why/ you’re pursuing a goal.

- If I achieved X, how would I use it?

- What features of X are the most important for me?

- Would a weaker/simpler version of X suffice?

-

On Goals:

- Goals for some people are a source of energy and motivation, however it’s important to make sure you have full awareness of the impact the goal definition will have on you. As an example: perhaps you’re playing a game competitively, and you define a goal of “I want to beat player X, or I want to achieve rank Y”. Failing at one instance of the game might generate negative emotional impact “I’m a failure, because this means I’m not achieving my goal”. Redefining the goal as “I want to achieve excellence in this game, and that means learning from success and failure” can alter the emotional reaction.

- Identify where a goal may be causing emotional stress, then look at the questions above: “What features of the goal are most important for me?” and “Would a weaker/simpler version of X suffice?”.

-

All warfare is based on deception.

-

Know when you’ve already won, and if you have, stop fighting, even if your opponent wants to keep going (this is a common strategy in Go apparently).

-

Inversion: ‘Invert, always invert’. Examine problems backwards as well as forwards.

- Facebook IPO: 50 billion. To grow to the biggest company in the world, it needs to hit $380 billion. In order to do that, it would need to generate a 22% growth rate per year for 10 years as a ‘maximum upside’. Compared to the market of 8%, that’s not quite a rosy a picture as one would want for the risk. Inversion is taking a problem and working it backwards to a solution.

-

What matters more in decisions? Analysis or Process?

- Both, but process matters more: you can have amazing analysis and poor process and therefore poor outcomes, but poor analysis and amazing process will by default weed out poor analysis.

- Imagine a courtroom trial that consists of the prosecutor presenting PowerPoint slides, in 20 compelling charts he says why the defendant is guilty. The judge challenges some questions (prosecutor has good answers), and then rules guilty and we’re done. This process is shocking. Cross-examination matters.

-

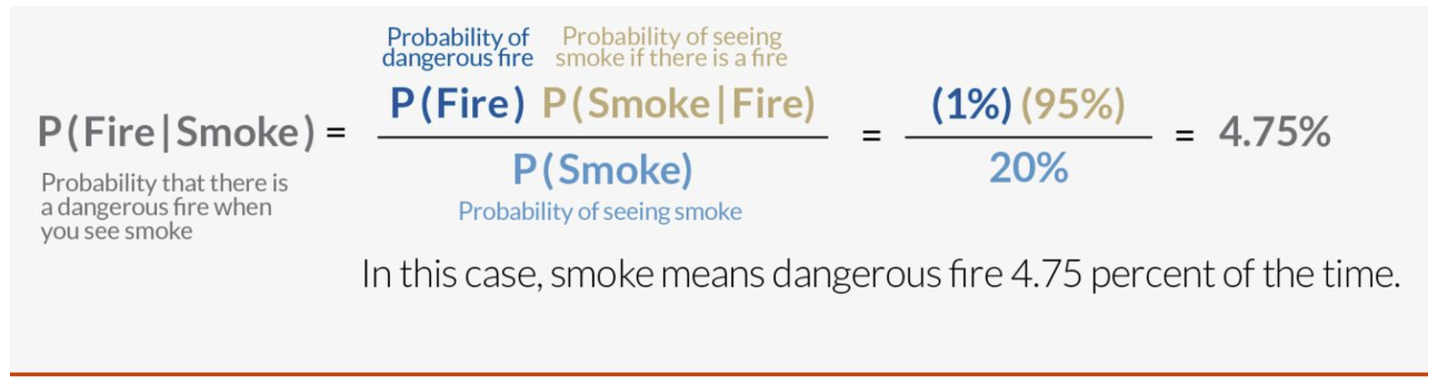

Be sensitive to base rates: “Donald is either a librarian or a salesman. His personality can best be described as ‘retiring’. What are the odds he is a librarian?”. Salesman outnumber libraries 100:1 (1% base rate). (Bayes).

-

‘Mimicking the herd invites regression to the mean’. If you act average, you will be average.

-

Two track analysis: What are the facts? And where is my brain fooling me?

-

Measurement:

- We should care about measurement because it informs key, but uncertain decisions.

- Measurement is the methods and process for reducing uncertainty.

- Define the decision; Determine what you know now; Compute the value of additional information; Measure where information value is high; Make the decision and act. Rinse repeat.

- Soft, touchy-feely-sounding-things like ’employee empowerment’, ‘creativity’ or ‘strategic alignment’ must have observable consequences if they matter at all.

- Measurement: a quantitatively expressed reduction of uncertainty based on one or more observations.

- Uncertainty: The existence of more than one possibility where the ’true’ outcome is not known. Measurement of uncertainty is a set of probabilities.

- Risk: a state of uncertainty where some possibilities involve a loss or catastrophe or undesirable outcome. Measurement of risk is a set of quantified probabilities with quantified losses.

-

Goals vs. Systems:

- Talked about here (http://blog.dilbert.com/2013/11/18/goals-vs-systems/), Scott Adams talks about using systems instead of goals. His example: losing ten pounds is a goal (that most people can’t maintain), whereas learning to eat right is a system that substitutes knowledge for willpower. Going to the gym 3-4 times a week is a goal, but if you don’t enjoy exercise it’ll be hard to achieve and maintain. Compare that with a system of being active every day of the week with an activity that feels good – the system will be more effective in achieving the outcome you want.

Your Role⌗

-

Tune your managers to managerial excellence

-

Recognize that you’re overseeing management as opposed to other types of work.

- Rely on the observations and reports of others, rather than directly experiencing situations

-

You’re now out of the business of ‘how’ and in to the business of ‘why’.

-

You’re signaling even more, character matters. The team may start to copy your behavior. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_cognitive_theory]

- And they’re constantly looking signals of appreciation, recognition, leadership and more.

-

Your channeling your orgs values through your managers

-

As Jay Parikh would say, “Scale yourself!”

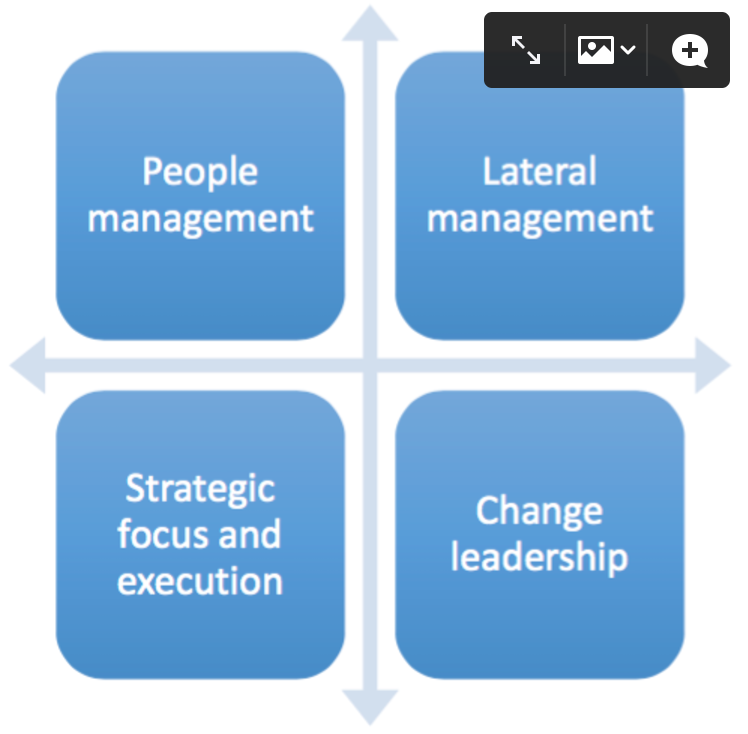

- Strategic focus and execution:

- Just like your managers, you should have a vision and a strategy, and that should map to the greater org strategy.

- In order to drive impact to the organization, you must be plugged in to the organization.

- Feed the ‘impact’ beast. Your team is hungry.

- This will take up about 2-3x more time than it used to.

- Lateral management:

- Oil the machinery for cross-team collaboration. Build relationships with managers and IC’s in other parts of the org and lean on those, particularly in times of crisis. Build peace time relationships.

- Your managers will be more inward focused than (particularly new ones). Anticipate this, build a feedback loop with that teams partners, channel that feedback.

- Change leadership:

- Change is hard, that’s why they pay you the big bucks.

- Steady the ship as she’s turnin’.

- People management:

- You’re mostly a coach now. Deal with it.

- Sometimes you need to be a passenger, even if you think the car is going to crash. More things are going to break than you can fix. Sometimes it’s okay to let them break. Arbitration between your teams needs and the organizational needs - you’re responsible for balancing those tradeoffs.

- Strategic focus and execution:

-

Anticipation of problems and opportunities is probably the single biggest value add you can bring to your team

-

Understand what system and culture you’re operating within:

- (Blatently lifted from [https://steveblank.com/2018/04/23/why-the-future-of-tesla-may-depend-on-knowing-what-happened-to-billy-durant/]):

- The modern corporate structure can be traced back to Alfred P. Sloan, who was president of General Motors from 1923 to 1956 when the U.S automotive industry grew to become one of the drivers of the U.S economy.

- Sloan was the first to work out how to systematically organize a big company. He put in place planning, strategy, measurements and most importantly, the principles of decentralization.

- When Sloan arrived at GM in 1920 he realized that the traditional centralized management structures organized by function (sales, manufacturing, distribution, and marketing) were a poor fit for managing GM’s diverse product lines. That year, as management tried to coordinate all the operating details across all the divisions, the company almost went bankrupt when poor planning led to excess inventory, with unsold cars piling up at dealers and the company running out of cash.

- Borrowing from organizational experiments pioneered at DuPont (run by his board chair), Sloan organized the company by division rather than function and transferred responsibility down from corporate into each of the operating divisions (Chevrolet, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Buick and Cadillac). Each of these GM divisions focused on its own day-to-day operations with each division general manager responsible for the division’s profit and loss. Sloan kept the corporate staff small and focused on policymaking, corporate finance, and planning. Sloan had each of the divisions start systematic strategic planning. Today, we take for granted divisionalization as a form of corporate organization, but in 1920, other than DuPont, almost every large corporation was organized by function.

- Sloan put in place GM’s management accounting system (also borrowed from DuPont) that for the first time allowed the company to: 1) produce an annual operating forecast that compared each division’s forecast (revenue, costs, capital requirements and return on investment) with the company’s financial goals. 2) Provide corporate management with near real-time divisional sales reports and budgets that indicated when they deviated from plan. 3) Allowed management to allocate resources and compensation among divisions based on a standard set of corporate-wide performance criteria.

-

Failure for a manager to identify where they are on the response spectrum of ‘arrogant’, ‘balanced/objective’, ‘imposter’ and ’naive/ignorant’:

- Consider this scenario: an IC report who was performing well is put into a new situation outside of their comfort zone and/or strengths. The IC begins to struggle, and is unable to root cause for themselves why they are struggling. They start to push hard (and possibly emotionally) on their manager to ‘fix things’, but they do it in a non-obvious way: they start raising issues and problems that they’re seeing in the team, the situation, and with the manager. The differences in manager response based on the spectrum can be quite diverse:

- Arrogant: these problems aren’t problems, the real problem is the IC’s inability to deal with the situation. Interprets IC feedback as criticism. Believes IC is ‘blaming others’ and not taking responsibility. Leverages power-imbalance between IC and manager. Possible outcome: manager gives “feedback” to IC that they’re raising problems, not solutions and that they should own it more (or some such). Problems get worse until they hit a pain threshold for either the manager or IC. IC gets fired or IC quits. Manager hasn’t reflected on the possibility that it may be their own skill gap (switching from coaching to directive for instance) that caused the problem.

- Imposter: these problems are criticisms of me and my ability to manage this style of person. Possible outcome: real root cause unaddressed, over-pivot to trying to own the problems and emotions on behalf of the IC, communication to IC that they’re not at fault. Possible quick ’re-pivoting’ of the IC’s work/situation to avoid the situation. Missed opportunity for coaching/growth of the IC.

- Naive/ignorant: these problems seem like they’re temporary and perhaps unimportant. Once this person “grows”, they’ll overcome them. Possible outcome: IC quits. Manager will eventually get fired.

- Balanced: manager reflects on a range of possible root causes here: IC isn’t criticizing, they’re struggling and unsafe, and struggling to articulate that they need help; my management style isn’t appropriate for this person given this situation; this person may be lacking skills or capability or maturity to deal with this situation and needs direct feedback; this may be a performance problem that needs to be managed; this may be a broader problem (team culture issue, relationship issue etc). Possible outcome: a higher probability of root causing real issue; installs higher signal ‘feedback loops’ which increase safety and increase probability of IC being successful or failing fast if required. Manager learns how to adjust style faster. Leads to better outcome for both manager and IC.

- Managers with more experience seem to have a higher likelihood of drifting into ‘arrogance’ and not identifying that.

- These different categories are possibly related to one’s default ego bias.

- Arrogance is a more dangerous form of naivety (naive people can be ‘woken’, arrogance tends to be stubborn). Both are dangerous for IC’s regardless.

- How do you identify where you are in the spectrum? How about others?

- Consider this scenario: an IC report who was performing well is put into a new situation outside of their comfort zone and/or strengths. The IC begins to struggle, and is unable to root cause for themselves why they are struggling. They start to push hard (and possibly emotionally) on their manager to ‘fix things’, but they do it in a non-obvious way: they start raising issues and problems that they’re seeing in the team, the situation, and with the manager. The differences in manager response based on the spectrum can be quite diverse:

Notes on Team Execution: Lockdowns⌗

[Written within a FAANG Infrastructure group around ~2015]

Given Infra is in lockdown right now, we thought we’d share our recipe for lockdown success. It’s by no means the only tasty recipe in town, so you should fork and customize for your own situation. Enjoy.

Ingredients:

- A very clear “not sure we can achieve it, but fuck it’s close” goal.

- ‘x’ hungry engineers that really want to achieve the goal.

- A fixed, short time period, calendars cleared.

- A endorphin inducing feedback loop, injected daily.

- Strong “war cry” leaders that leave no person behind.

- Pizza and beer.

The compiler team has completed four lockdown’s in the past two years and loved three out of the four, and sorta liked the fourth. The first one we did is what kicked off the tradition, and that was in response to the new compiler being significantly slower than the previous compiler (60% of the throughput…) and no good ideas as to why. We “locked down” with a janky and made up process, a lot of motivation, but not a lot of belief that it’d help us over the line. We clawed our way to 100% parity in 6 weeks (and an extra ~10% on top of that soon after), and we’ve been doing it ever since. Here’s how we do it, and what we’ve learned:

Build Awareness⌗

- Book a different space. Move people. Important to get people out of their day-to-day locations.

- Set expectations early that a lockdown is coming. Schedules cleared etc.

- Build excitement by mentioning it a lot at meetings and whatnot. Talk to other teams, ask if others want to join.

Build Out the Process⌗

The process we use to run our lockdowns is the “endorphin inducing feedback loop”, which in turn builds a lot of momentum and intensity for the lockdown period. Ours is crafted to induce a few behaviors within the team that we don’t typically see outside lockdown: 1) emphasis on small, incremental wins that sum up to hitting the goal, 2) lots of rich communication between team members, 3) making it okay to fail. The process we built out is a weird derivative of “agile”, and it looks like this:

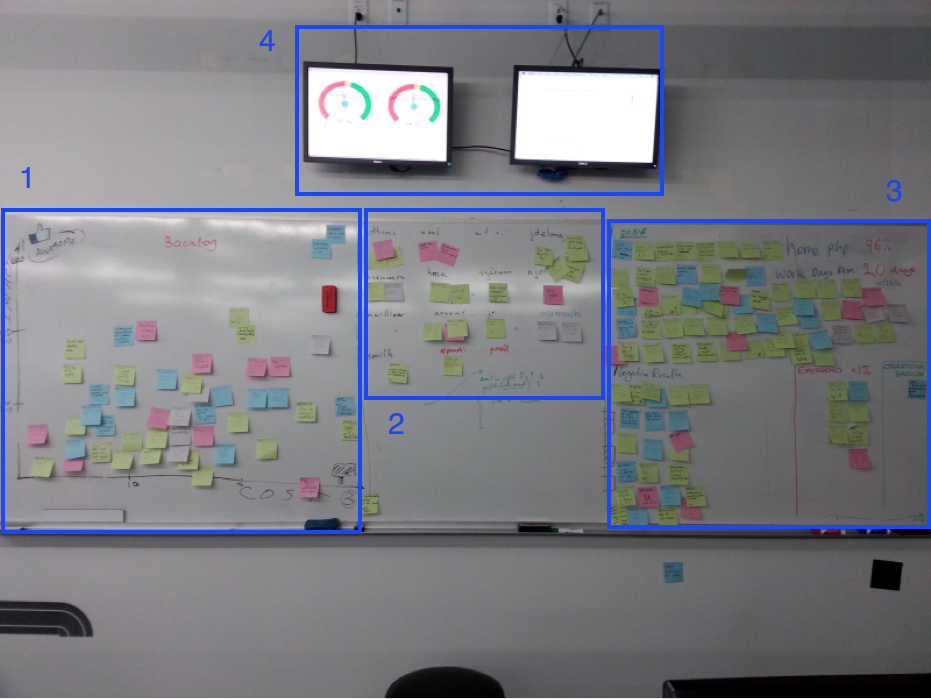

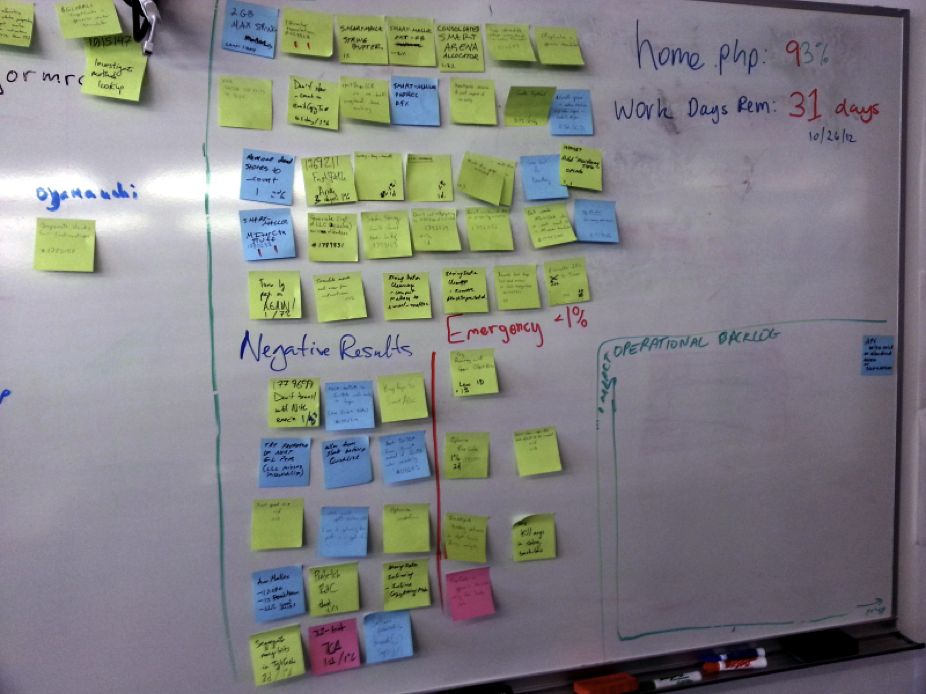

We have four sections of a whiteboard: (1) is the backlog of tasks and activities we’re going to go after described by stickies (colors don’t actually matter), (2) contains a list of engineers and the tasks (stickies) they’re currently working on, (3) is what we’ve completed so far, divided in two buckets: done, and negative results, and (4) a graph of where we’re at right now relative to the goal.

So what’s going on here?

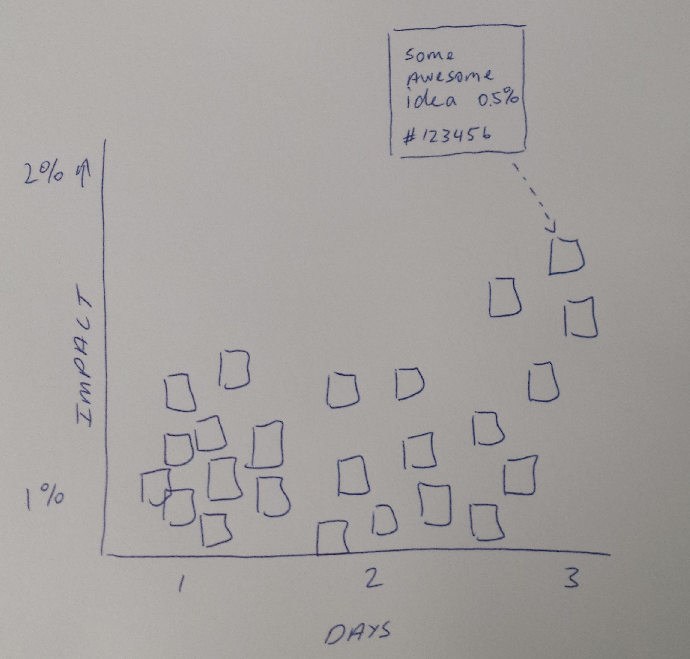

Backlog⌗

This whiteboard section contains a two dimensional area where ideas for lockdown are plotted using stickies. We generate the ideas through several brainstorming sessions, and we constrain the ideas generated by limiting the ‘x’ and ‘y’ axis. For compiler lockdowns, the ‘x’ axis constrains the amount of time we want to spend on these tasks, and the ‘y’ axis forces us to estimate the impact on the goal. We chose three days as the limit to drive the behavior of incremental tuning, as opposed to new feature development or refactoring.

We tag the sticky with a task number and the summary of what the idea is. Here’s what it looks like close up:

We typically have at least two brainstorming sessions (a couple of hours long) before the lockdown begins. It’s important to space them a day or two apart, so engineers have time to think about ideas in the shower and what not. During lockdown, we continue to hold brainstorming sessions (usually one a week) to keep the two dimensional space full and up to date. It is important to do these as a group, because the quality & position of the ideas is much higher from immediate group feedback, than if they were placed individually. The conversation usually spurs new ideas.

Who’s Working on What⌗

This section is very simple. It contains a list of engineers unix handles and shows exactly which stickies they’re working on right now. We make sure nobody is holding on to more than 2-3 at a time.

What’s Done⌗

This section is divided up into two spaces: “done” and “negative results”. For the compiler, this is important because it provides the team with signal on what ideas have been profitable vs. not and allows engineers to prioritize other ideas that are similar to profitable ones. It also makes it very clear that ideas which failed to produce results are useful signal, and therefore valuable.

Are We There Yet?⌗

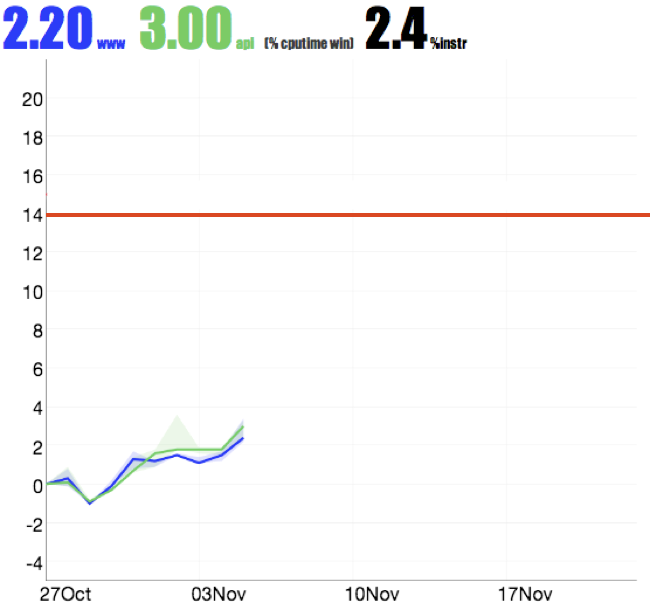

Arguably the most important ingredient of the process we use is a graph tracking how we’re doing relative to the lockdown goal. We display this at all times, and update once a morning. This is a major source of the “endorphin inducing feedback loop” and our lockdowns would undoubtedly be less successful without one:

The Mechanics⌗

During the weeks of lockdown we cycle through this simple mechanic: brainstorm ideas, plot them on the backlog graph, engineers pull them off and put them next to their names, and when they’ve tested the idea they put it in the “done” or “negative result” section. Rinsing and repeating this process drives the graph up and to the right. What this doesn’t tell you is exactly what it feels like to be in the room while the mechanics take place. This is what you can expect:

- Constraining the ‘x’ and ‘y’ axis means brainstorming sessions don’t go off the rails. When an idea is pitched and its deemed longer than the time constraint it gets put on the “post lockdown” backlog. These sessions usually trigger an early sense of excitement and anticipation.

- Stickies on the two dimensional plot have two interesting side-effects: 1) the team ‘blesses’ the amount of time we should be spending on a given task and empower any engineer to fail fast after the time is up, and 2) stickies in this space have no owner and allow any engineer to simply walk up, grab a sticky and get to work. There is no fucking around with engineers second guessing themselves.

- When an engineer does walk up to the stickies board to either grab a sticky, or move it to the “done” bucket, all eyes in the room are fixed on what they’ll pick off next, or where the sticky ends up. This leads to conversations about the task immediately, and usually follow up stickies are generated in discussion.

- Engineers showing up in the morning immediately check the graph and start chatting about the effect of yesterday’s work. They feel excited about the graph moving in the right direction, and motivated to keep pushing.

- It’s very easy to see how hard your teammates are working (it’s right there on the board) and it creates a bit of a social contract to not fuck around and not slack off.

- There’s a lot of positive team reinforcement, “great job!” type thing. Leadership often arises from unexpected people.

- The amount of conversation that takes place between engineers is the biggest game changer.

What Can Go Wrong?⌗

Our last lockdown was good, but it wasn’t as great as the last three. We actually hit our goal, but the measure of success for us includes how we felt about the lockdown, and we felt good but not great about it. Here’s a few “antipatterns” we’ve learned:

- Friction in the “endorphin inducing feedback loop” causes a lot of frustration. For us the tooling in our workflow was broken a lot during the last lockdown so we were often blind to how we were going day-to-day.

- You are what you measure. Graphs are a proxy for what you care about. If you don’t have faith that the proxy is a real reflection of the goal you want to achieve, you won’t get that endorphin buzz.

- There needs to be strong belief throughout the team that the desperate slog you’re in right now is deeply appreciated by the company (handy tip: invite Jay to your lockdown and ask him to bring beers - it’s a nice morale boost).

GOOD LUCK!

Random Notes⌗

TODO: clean all these up, integrate them into the themes above.

Thinking about Thinking⌗

Charles Darwin (from [https://www.fs.blog/2016/10/charles-darwins-reflections-mind/]):

- He did not have a quick intellect or an ability to follow long, complex or mathematical reasoning. If you’re aware of your limitations, you can counter-weight it with other methods.

- “I have no great quickness of apprehension or wit which is so remarkable in some clever men, for instance, Huxley. I am therefore a poor critic: a paper or book, when first read, generally excites my admiration, and it is only after considerable reflection that I perceive the weak points. My power to follow a long and purely abstract train of thought is very limited; and therefore I could never have succeeded with metaphysics or mathematics. My memory is extensive, yet hazy: it suffices to make me cautious by vaguely telling me that I have observed or read something opposed to the conclusion which I am drawing, or on the other hand in favour of it; and after a time I can generally recollect where to search for my authority. So poor in one sense is my memory, that I have never been able to remember for more than a few days a single date or a line of poetry.”

- He did not feel easily able to write clearly and concisely. He compensated by getting things down quickly and then coming back to them later, thinking them through again and again.

- He forced himself to be an incredibly effective and organized collector of information.

- “As in several of my books facts observed by others have been very extensively used, and as I have always had several quite distinct subjects in hand at the same time, I may mention that I keep from thirty to forty large portfolios, in cabinets with labelled shelves, into which I can at once put a detached reference or memorandum. I have bought many books, and at their ends I make an index of all the facts that concern my work; or, if the book is not my own, write out a separate abstract, and of such abstracts I have a large drawer full. Before beginning on any subject I look to all the short indexes and make a general and classified index, and by taking the one or more proper portfolios I have all the information collected during my life ready for use. I have no great quickness of apprehension or wit which is so remarkable in some clever men, for instance, Huxley. I am therefore a poor critic: a paper or book, when first read, generally excites my admiration, and it is only after considerable reflection that I perceive the weak points. My power to follow a long and purely abstract train of thought is very limited; and therefore I could never have succeeded with metaphysics or mathematics. My memory is extensive, yet hazy: it suffices to make me cautious by vaguely telling me that I have observed or read something opposed to the conclusion which I am drawing, or on the other hand in favour of it; and after a time I can generally recollect where to search for my authority. So poor in one sense is my memory, that I have never been able to remember for more than a few days a single date or a line of poetry.”

Imposter syndrome:⌗

- “Inability to internalize their accomplishments and a persistent fear of being exposed as a fraud”

- “Chronic self-doubt”

- “Confidence issue”

- “Rational response to insufficient feedback”

Quippy Mental Models:⌗

-

Avoid Stupidity: “we continue to try more to profit from always remembering the obvious than from grasping the esoteric. … It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent. There must be some wisdom in the folk saying, `It’s the strong swimmers who drown.’”

-

You must do hard things that create value. Being a taskmaster isn’t going to cut it anymore.

-

https://www.farnamstreetblog.com/2016/10/charles-darwins-reflections-mind/

-

Plans are maps that we become attached to. Scrap them, isolate the key variables that you need to maximize and minimize.

-

We seek competition as validation. Instead of going through the small door that everyone is rushing towards, try going around the back. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Fx5Q8xGU8k

-

Tell me something that is true, that very few people agree with you on.

-

Domino theory of reality: small incremental steps in a story to take you from reality, to the surreal.

-

We all have things that we value that we want and we all have strengths and weaknesses that affect our paths for getting them. The most important quality that differentiates successful people from unsuccessful people is our capacity to learn and adapt to these things.

-

“How much do you let what you wish to be true stand in the way of seeing what is really true?”

-

People who overweigh the first-order consequences of their decisions and ignore the effects that the second- and subsequent-order consequences will have on their goals rarely reach their goals. For example, the first-order consequences of exercise (pain and time-sink) are commonly considered undesirable, while the second-order consequences (better health and more attractive appearance) are desirable

-

To achieve your goals, you have to prioritize, and that includes rejecting good alternatives.

-

Avoid setting goals based on what you think you can achieve.

-

“Most problems are potential improvements screaming at you”. The more painful the problem, the more it is screaming. To be successful, you need to perceive and then not tolerate problems. It is essential (and usually painful) to bring these problems to the surface.

-

To perceive problems, compare how the movie is unfolding relative to your script.

-

Ask yourself what is your biggest weakness that stands in the way of what you want.

-

(https://www.gwern.net/docs/iq/1996-jensen.pdf): Creativity comes from three sources of variance: (1) ideational fluency, or the capacity to tap a flow of relevant ideas, themes, or images, and to play with them, also known as “brainstorming”; (2) what Eysenck (1995) has termed the individuals’ relevance horizon; that is, the range or variety of elements, ideas, and associations that seem relevant to the problem (creativity involves wide relevance horizon); and (3) suspension of critical judgment. Creative persons are intellectually high risk takers.

-

On critical thinking: Learn to write, then write! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pY8MlNJrlug

-

Really Understand Bayes!

-

Get ‘unstuck’: Start with Problem Finding, then problem solving (design thinking). (https://www.npr.org/2017/01/03/507901716/how-silicon-valley-can-help-you-get-unstuck)

- Tame problems (know what to solve)

- Wicked problem (problems are highly dynamic, things are changing all the time). Wicked problems are great for design thinking – iterating multiple ideas with prototypes. You don’t have a map for solving the problem, you need to ‘way find’. He believes ’life design’ is a wicked problem. You may not have one destination. There is many right answers to the question of ‘what does your life look like’.

- Build three different pictures of your next 5 years.

- Create a set of prototypes around these three pictures.

- Then pick one. People feel better about their choices once they’ve articulated the available set of options and then chosen the best.

- ‘Design it as you go along’.

- Design is orientated to action. Classify and ignore ‘gravity’ constraints (i.e. things you can’t do anything about). Accept gravity circumstances (they’re circumstances, not problems to solve) as fact.

- Look honestly at your circumstances, then figure out what room you have to maneuver.

- Fail early and often.

Notes from Principles:⌗

-

Principles is an underrated book. Here are some notes from it:

-

Experience taught me how invaluable it is to reflect on and write down my decision-making criteria whenever I made a decision, so I got in the habit of doing that. With time, my collection of principles became like a collection of recipes for decision making.

-

“five steps”:

- Set clear goals

- Identify and don’t tolerate the problems that stand in the way of achieving those goals

- Accurately diagnose these problems

- Design plans that explicitly lay out tasks that will get around your problems and on to your goals

- Implement these plans. Do the tasks.

-

Have clear goals. Prioritize. You can’t have everything you want.

-

Decide what you really want in life by reconciling your goals and your desires. What will ultimately fulfill you are things that feel right at both levels, both desires and goals.

-

Almost nothing can stop you from succeeding if you have a) flexibility and b) self-accountability. Flexibility is what allows you to accept what reality (or knowledgeable people) teaches you; self-accountability is really believing that failing to achieve a goal is your personal failure, you will see your failing to achieve it as indicative that you haven’t been creative or flexible or determined enough to do what it takes. And you will be much more motivated to find the way.

-

Problems

- View painful problems as potential improvements that are screaming at you. Each and every problem you encounter is an opportunity; for that reason, it is essential that you bring them to the surface.

- Be specific in identifying your problems: you need to be precise, because different problems have different solutions.

- Don’t mistake a cause of a problem with the real problem.

- Distinguish big problems from small ones. Then prioritize.

- Once you identify a problem, don’t tolerate it.

-

Diagnosing problems:

- Focus on the ‘what is’ before deciding ‘what to do about it’. Good diagnosis takes between 15 minutes and an hour depending on how well its done and its complexity. Gather evidence, determine root cause. Like principles, root causes manifest themselves over and over again in seemingly different situations. Finding them and dealing with them pays dividends again and again.

- Distinguish proximate causes from root causes. Proximate causes are typically the actions (or lack of actions) that lead to problems, so they are described with vers (I missed the train because I didn’t check the train schedule) vs. (I didn’t check the train schedule because I’m forgetful). You can only truly solve your problems by removing their root causes and to do that, you must distinguish the symptoms from the disease.

- Recognizing that knowing what someone is like will tell you what you can expect from them.

-

Plan:

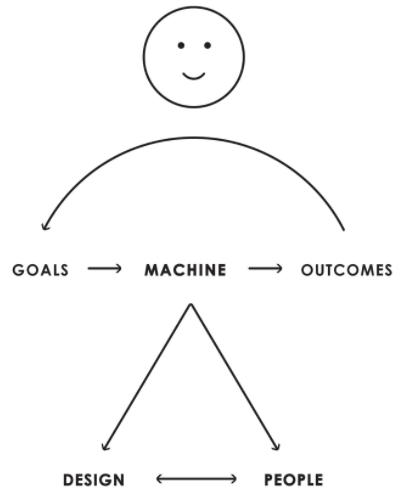

- Think about your problem as a set of outcomes produced by a machine. Practice higher level thinking by looking down on your machine and thinking about how it can be changed to produce better outcomes.

- Remember that there are typically many paths to achieving your goals

- Think of your plan as being like a movie script in that you visualize who will do what through time.

- Write down your plan for everyone to see and to measure your progress against.

-

Push to completion:

- Establish clear metrics to make certain that you are following your plan.

-

You will need to synthesize and shape well. The first three steps (setting goals, identifying problems, and diagnosing them) are synthesizing (by which I mean knowing where you want to go and what’s really going on). Designing solutions and making sure that the designs are implemented are shaping.

-

Everyone has at least one big thing that stands in the way of their success; find yours and deal with it. Write down what your one big thing is (such as identifying problems, designing solutions, pushing through to results) and why it exists (your emotions trip you up, you can’t visualize adequate possibilities). While you and most people probably have more than one major impediment, if you can remove or get around that one really big one, you will hugely improve your life.

-

The key to success lies in knowing how to both strive for a lot and fail well. By failing well, I mean being able to experience painful failures that provide big learnings without failing badly enough to get knocked out of the game.

-

“How do I know I’m right?”

-

Reflect on and write down your decision making criteria. With time your collection of principles will become a collection of recipes for decision making

-

Systematize your decision making. Encode them in rules, or programs.

-

When faced with the choice between two things you need that are seemingly at odds, go slowly to figure out how you can have as much of both as possible.

-

Shapers: all independent thinkers who do not let anything or anyone stand in the way of achieving their audacious goals. They have strong mental maps of how things should be done, and at the same time willingness to test those mental maps in the world of reality and change the ways they do things to make them work better. Able to see big picture and granular details (and levels in between) and synthesize the perspectives they gain at those different levels. Assertive, open minded, intolerant of people who work for them who aren’t excellent at what they do.

-

By knowing what someone is like we can have a pretty good idea of what we can expect from them.

-

Good habits come from thinking repeatedly in a principled way, like learning to speak a language. Good thinking comes from exploring the reasoning behind the principles.

-

Some people want to change the world and others want to operate in simple harmony with it and savor life. Neither is better. Each of us needs to decide what we value most and choose the paths we take to achieve it.

-

When trying to understand anything, economies, markets, the weather, whatever, one can approach the subject with two perspectives:

- Top down: By trying to find the one code/law that drives them all. For example, in the case of markets, one could study universal laws like supply and demand that affect all economies and markets. In the case of species, one could focus on learning how the genetic code (DNA) works for all species.

- Bottom up: By studying each specific case and the codes/laws that are true for them, for example the codes or laws particular to the market for wheat or the DNA sequences that make ducks different from other species.

-

Don’t get hung up on your views of how things ‘should’ be because you will miss out on learning how they really are. Whenever I observe something in nature that I (or mankind) think is wrong, I assume that “I’m wrong” and try and figure out what nature is doing makes sense.

-

Go to pain rather than avoid it: don’t let up on yourself and instead become comfortable always operating with some level of pain, you will evolve at a faster pace. Every time you confront something painful, you are at a potentially important juncture in your life – you have the opportunity to choose healthy and painful truth, or unhealthy but comfortable delusion.

-

No matter what you want in life, your ability to adapt and move quickly and efficiently through the process of personal evolution will determine your success and your happiness. If you do it well, you can change your psychological reaction to it so that what was painful can become something you crave.

-

Think of yourself as a machine operating within a machine and know that you have the ability to alter your machines to produce better outcomes.

-

By comparing your outcomes with your goals, you can determine how to modify your machine.

-

Distinguish between you as the designer of your machine and you as a worker with your machine. One of the hardest things for people to do is objectively look down on themselves within their circumstances (i.e. their machine) so that they can act as the machines designer and manager. To be successful, the designer/manager you has to be objective about the ‘worker you’ is really like, not believe in him more than he deserves or putting him in jobs he shouldn’t be in. Instead of having this strategic perspective, most people operate emotionally and in the moment; their lives are a series of undirected emotional experiences, going from one thing to the next. If you want to look back on your life and feel you’ve achieved what you wanted to, you can’t operate that way.

-

Successful people are those who can go above themselves to see things objectively and manage those things to shape change. They can take in the perspectives of others instead of being trapped in their own heads with their own biases.

-

When you encounter your weaknesses, you have four choices:

- You can deny them (which is what most people do)

- You can accept them and work at them in order to try and convert them into strengths (which might or might not work depending on your ability to change)

- You can accept your weaknesses and find ways around them

- Or, you can change what you’re going after.

-

Asking others who are strong in areas where you are weak to help you is a great skill that you should develop no matter what, as it will help you develop guardrails that will prevent you from doing what you shouldn’t be doing. All successful people are good at this.

Notes from Zero to One:⌗

-

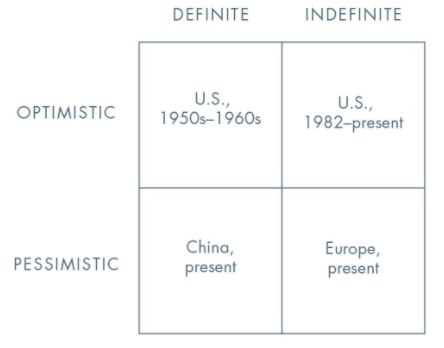

Zero to One is also a really underrated book. If you squint hard enough, it’s a book about psychology, philosophy and risk. Here are some notes:

-

Indefinite attidudes to the future explain what’s most dysfunctional in our world today. Process trumps substance: when people lack concrete plans to carry out, they use formal rules to assemble a portfolio of various options. [p61]

-

The indefiniteness of finance can be bizarre. Think about what happens when successful entrepreneurs sell their company. What do they do with the money? In a financialized world, it unfolds like this:

- Founders give it to a large bank. Bankers don’t know what to do with it, they diversify by spreading it across a portfolio of institutional investors. Institutional investors don’t know what to do with it, they they diversify it across stocks. Companies try and increase their share price by generating free cash flows. If they do, they issue dividends or buy back shares and the cycle repeats. At no point does anyone in the chain know what to do with money in the real economy. In an indefinite world, people actually prefer unlimited optionality; money is more valuable than anything you could possibly do with it. Only in a definite future is money a means to an end, not the end itself. [p69]

-

Indefinite pessimism works because it’s self-fulfilling: if you’re a slacker with low expectations, they’ll probably be met. But indefinite optimism seems inherently unsustainable: how can the future get better if no one plans for it.

-

Remember our contrarian question: what important truth do very few people agree with you on? If we already understand as much of the natural world as we ever will then there are no good answers. Contrarian thinking doesn’t make any sense unless the world still has secrets left to give up:

-

Risk aversion: people are scared of secrets because they are scared of being wrong. By definition, a secret hasn’t been vetted by the mainstream. If your goal is to never make a mistake in your life, you shouldn’t look for secrets.

-

Secrets about people are relatively underappreciated. Maybe that’s because you don’t need a dozen years of higher education to ask the questions to uncover them: What are people not allowed to talk about? What is forbidden or taboo?

Assessing People, Situations, Decisions:⌗

People:

- Are they open minded or closed minded?

- Open minded: more curious about why there is disagreement. Believe they can be wrong.

- Closed minded: don’t want their ideas challenged. Frustrated when they can’t get the other person to agree with them instead of being curious about why the other person disagrees (this is somewhat in conflict with the emotional need of feeling heard). Block others from speaking.

- Easiest diagnosis criteria: ratio of questions/listening to explanation.

Example of simple mental model to complex:

- Performance review and compensation. What is your mental model, and what are the variables in it?

- The most simple model:

- The people that work for you have the same belief system about performance reviews and compensation as you do, and they act based on that.

- And the most common belief for managers is this: I’m here for the mission, so compensation matters less; Performance reviews are designed to give me clear and actionable feedback so I can grow in my career and job.

- Sometimes it’s “compensation doesn’t matter to me at all, and I’m suspicious of anyone for whom it does matter”.

- Corporate Politics:

- Thiel in this video [https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=649&v=a9Ts4_65hKk] talks about ‘We’re in many bubbles’.

- https://twitter.com/moskov/status/982287044880744448

- Interesting response to “assume good intent”: https://thebias.com/2017/09/26/how-good-intent-undermines-diversity-and-inclusion/amp/

Resources:⌗

- Sources of Power (How people make decisions) http://www.amazon.com/dp/B002V1I69S/

- Ferguson’s Formula (Alex Ferguson, Manchester United Coach) https://hbr.org/2013/10/fergusons-formula/ar/1

- (The follow up to this is “Life of Ryan: Caretaker Manager” http://www.imdb.com/title/tt3706190/. An interesting look at a “post Ferguson” era.

- Zero to One: http://www.amazon.com/Zero-One-Notes-Startups-Future-ebook/dp/B00J6YBOFQ

- The Art of Strategy: http://www.amazon.com/The-Art-Strategy-Theorists-Business/dp/0393337170

- Competitive Strategy: http://www.amazon.com/Competitive-Strategy-Techniques-Industries-Competitors-ebook/dp/B001CB34J0

- Interesting Links:

- https://www.theeffectiveengineer.com/book

- http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/04/mixed-signals-why-people-misunderstand-each-other/391053/

- https://medium.com/@evolvable/how-to-avoid-making-huge-mistakes-with-life-s-big-decisions-2e9a71af00bc

- http://blog.hut8labs.com/coding-fast-and-slow.html

- https://blog.bufferapp.com/the-mistake-smart-people-make-being-in-motion-vs-taking-action

- http://larch-www.lcs.mit.edu:8001/~corbato/turing91/

- https://hbr.org/2005/04/how-strategists-really-think-tapping-the-power-of-analogy [1]

- http://www.sirlin.net/articles/writing-well-part-2-clear-thinking-clear-writing [2]

- http://jamesclear.com/eisenhower-box [3]

Advanced: Transactional Analysis⌗

-

[Transactional Analysis is a pretty fringe part of psychology, but it’s probably worth a bit of time to study given it has systems for categorization and transitions of behaviors which can be useful mental models to port to different social contexts].

-

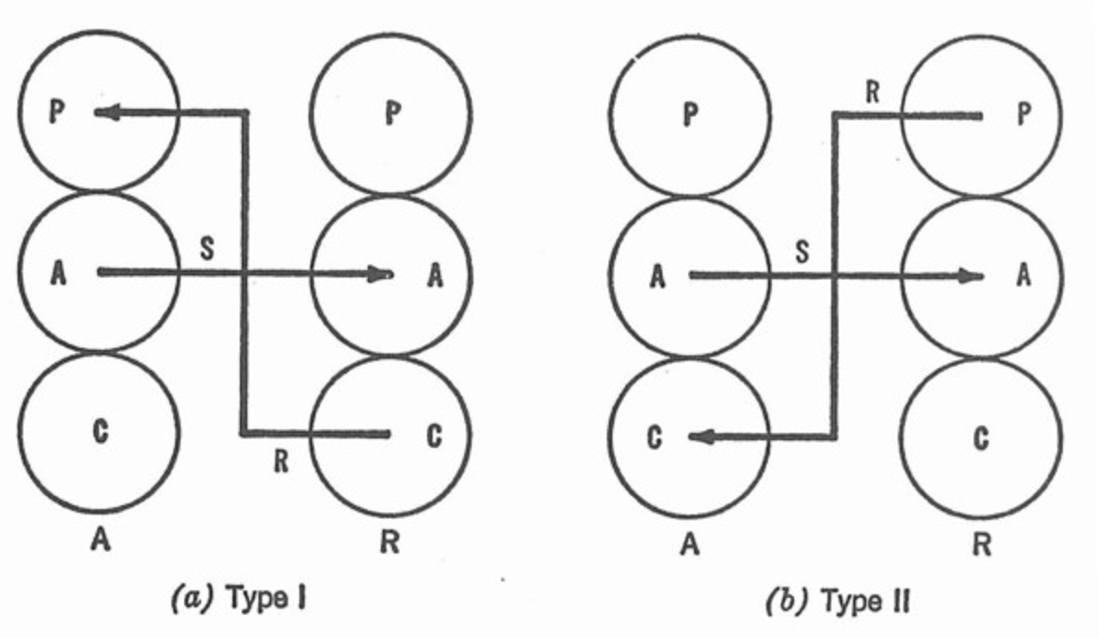

Observation of spontaneous social activity reveals that from time to time people show noticeable changes in posture, viewpoint, voice, vocabulary and other aspects of behavior. These behavioural changes are often accompanied by shifts in feeling. In an individual, a certain set of behaviors corresponds to one state of mind, while another set is related to a different psychic attitude, usually inconsistent with the first. These changes and differences give rise to the idea of ego states.

-

Ego states:

- Parent: ego states which resemble the ego states of his parents “everyone carries his parents around inside him”. Parent comes in two forms: directly active (person responds as his own father or mother would) and indirect influence (responds the way they wanted him to respond)

- Adult: ego state capable of objective data processing. Rational. Task of an adult is to regulate the activities of the Parent and the Child and to mediate objectively between them.

- Child: ego states carried within a person which are fixated relics from earlier childhood years. Not ‘childish’. Child state can contribute to the individuals life: charm, pleasure, creativity, but if the child is confused and unhealthy, consequences may be unfortunate. Two forms: adaptive child (modifies his behavior under the Parental influence, behaves as they’d have wanted him to behave) and natural child (spontaneous expression: rebellion or creativity).

-

All three states have a high survival and living value. It’s only when one disturbs the healthy balance that analysis and reorganization are needed. Otherwise, each is entitled to equal respect and has its legitimate place in a full and productive life.

-

The first rule of communication is that communication will proceed smoothly as long as transactions are complementary; and its corollary is that as long as transactions are complementary, communication can, in principle, proceed indefinitely.

-

The converse rule is that communication is broken off when a crossed transaction occurs. The most common crossed transaction, and the one which causes the most social difficulties in the world (marriage, love friendship, work) is represented here:

- “Maybe we should find out why you’ve been drinking more lately?”. An Adult->Adult transaction would be “Maybe we should. I’d certainly like to know!”. A crossed transaction will be “You’re always criticizing me, just like my father did” or “you blame me for everything!”. The vectors cross, and in order to make forward progress, the talk must be suspended until the vectors can be realigned.

-

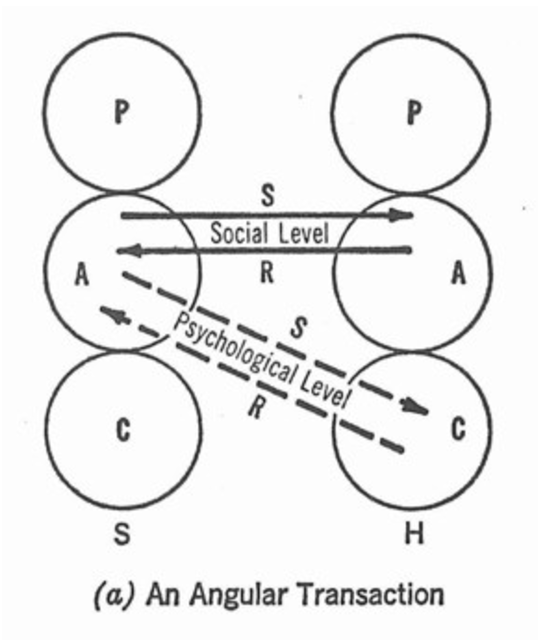

More complex transaction types: ulterior transactions (those involving the activity of more than two ego states simultaneously – the basis for games. Two examples: Angular transactions (Salesman: “This one is better, but you can’t afford it”, Customer: “That’s the one I’ll take”).

-

Salesman’s Adult has an ulterior motive: stimulate the response from the child to get the outcome he wants.

-

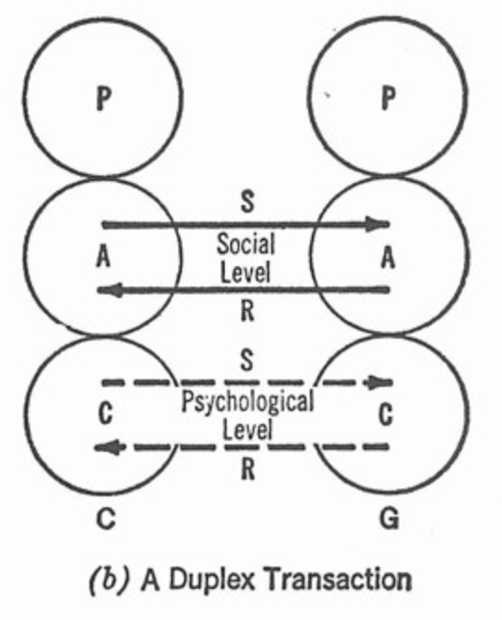

Duplex ulterior transaction:

-

Social transaction taken literally (come see the barn), Child response.

-